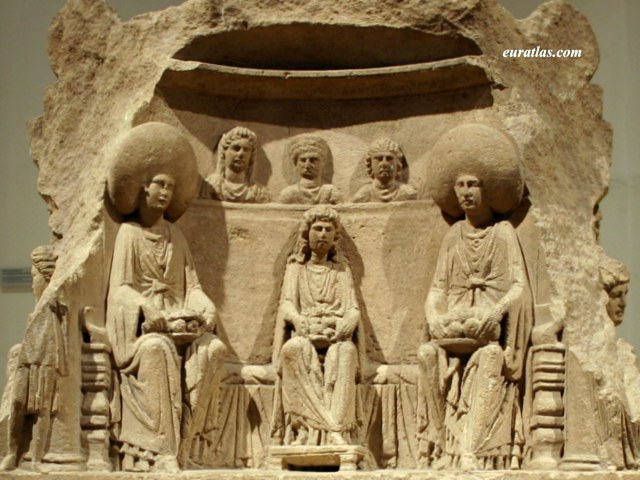

Matronae Aufaniae. Note the exaggerated headdresses on two of the figures, the short cloaks over longer dresses, shell shaped canopy overhead, and the bowls of fruit in their laps. While it is difficult to make out in this photo, they also all have crescent moon pendants around their necks and fibulae holding closed their cloaks.

http://www.livius.org/pictures/germany/nettersheim/dedication-to-the-aufanian-mothers/

While the Matronae and Matres are a collective of indigenous Germanic and Gaulish deities, they were worshipped by a broad cross-section of people in the Roman Empire using Roman religious structures, rituals, and concepts. It is understandable for modern polytheists who are trying to reconstruct old Germanic or Gaulish ways to try and “scrape the Roman trappings off” in an effort to distill Matronae or Matres worship back to its original roots. However, even if you choose to leave the Roman bits off in your modern practices, looking at the Roman trappings can provide us both with important layers of meaning as well as placing these Goddesses into a religious and cultural context in which they were worshipped for over 500 years.

The Matronae and Matres were worshipped in the Roman style from the first through fifth century AD. This “filter” was first described by Tacitus under the name Interpretatio Romana, in chapter 43 of his book Germania. He writes, when discussing the religious rites of a Germanic tribe, “Amongst the Naharvalians is shown a grove, sacred to devotion, extremely ancient. Over it a priest presides appareled like a woman; but according to the explication of the Romans (interpretatione romana), ‘tis Castor and Pollux who are here worshipped.” Interpretatio Romana can be understood as the “Roman articulation of an alien religion” (Irby-Massie, 1999). Under this concept, non-Roman deities were syncretized to Roman deities and, in places where indigenous religions continued to be practiced post-Roman conquest, were also fitted with Roman style rituals and religious trappings and framed within Roman cosmology.

In trying to understand or re-enliven Matronae and Matres worship, it is very useful to evaluate the Roman elements. The overlay of interpretatio Romana onto Matronae and Matres cults means that, despite there being no surviving written information about these goddesses, their rituals nor their worshippers, we can look at the iconography and the syncretism present in the remains of altars, statues and plaques and glean valuable information about these goddesses and this cult. Any Celtic or Germanic goddess who may have been understood as the Lady of the House became framed as a version of Juno; any goddess associated with sexuality, love or beauty became a face of Venus; any goddess associated with crops or harvesting became a face of Ceres, etc. And, given the well-defined and well-established lexicon of Roman artistic and symbolic “language” and the abundance of surviving Roman mythology, the symbols and images associated with these and other Roman goddesses found in Roman religious art are relatively consistent throughout the Roman Empire. This Roman syncretization gives us more insight into the interpretation of common symbols found in the Matronae and Matres statues, due to this consistency of iconographic meaning.

Iconographic Elements

As we evaluate the iconographic elements found in the Matronae and Matres artefacts, it is important to remember that the surviving stories that we have original versions of, and that were contemporary to this discussion, were the Roman ones. I have included references to later Germanic and Celtic stories, though the overwhelming majority of the written sources for the mythology of both of these cultures are generally from 500-1000 years after the fall of the Roman empire, and the end of Matronae worship as it was practiced in the Roman empire. We don’t know for certain whether the written Germanic and Celtic lore would have matched contemporary Germanic and Celtic lore from the period when the Matronae were worshipped. I have included it, however, because it provides context and insight into possible cultural understandings of these different symbols.

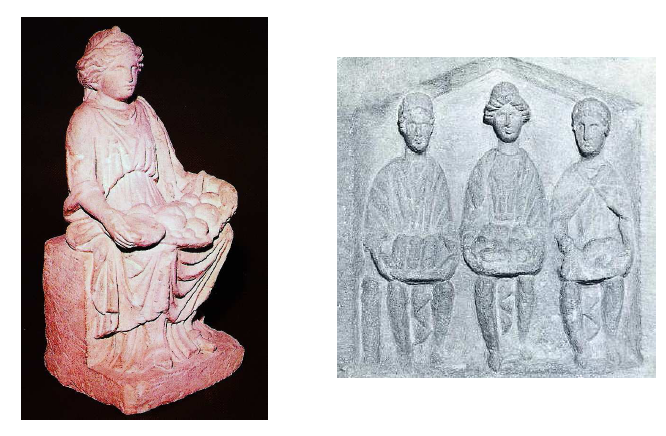

The Seated Female Figures:

The most common image found on these statues and altars are a depiction of three women, two wearing bonnets and one with her hair bared (though this is more commonly seen among Matronae carvings; Matres carvings sometimes have the women all with uncovered hair, depending on the region in which the artefact was found). Despite modern interpretations, this is not “maiden-mother-crone” imagery, as the images appear to be two married women on either side of an unmarried woman; all of whom appear to be of childbearing age. We don’t know why the women are arranged like this, though there are many theories. These three figures are generally depicted wearing linen dresses covered in short cloaks held closed by a fibula, and are often wearing necklaces with half or crescent moon shaped pendants. Two of the three woman wear very large linen bonnets. The clothing style is understood to be traditional Ubii fashion, even when the statues are found in regions that were not Ubii regions. As was discussed in an earlier article, the Ubii were a Germanic tribe who voluntarily joined the Roman empire, and Romanized early and thoroughly as compared to other non-Roman tribes (Garman, 2008).

While the artefacts clearly labeled “Matronae” most commonly show three seated female figures, several of the Matres statues include male/female god couples in affectionate poses, indicating a “sacred marriage” or a “wife-goddess and her consort”. Some Matres images also include nursing children, or with one or both breasts bared. The Nutrices plaques generally share attributes with the Matres images, and generally include bared breasts and nursing infants (Beck, 2009).

Given that the word “Matronae” can be translated as “matron, woman of status”, while “Matres” translates as an affectionate form of the word “mother”, it makes sense that we find different configurations for the seated figures depending on what name they are given. So, while “Matres” may have been goddesses associated with human fertility and family (or could be appealed to for help in those matters), “Matronae” may not have had this specific association.

In both Celtic and Roman traditions, when deities are depicted in triplicate, this generally implies great power – these were considered powerful deities (Garman, 2008). So the fact that these goddesses were depicted in triplicate didn’t necessarily mean there were three specific deities in any given Matronae or Matres group, but more likely simply implied that these goddesses functioned as a collective, and a powerful one. Later Celtic and Germanic mythology has numerous examples of deities found in triplicate, such as the Morrigan, the Norns, and some depictions of Odin, and these deities are generally given three individual names. There are no inscriptions indicating three specific and separate names for any of the Matronae or Matres goddesses, though there are a number of inscriptions that indicate specific goddess names. I’ll discuss inscriptions in another article.

Fruit, Coins, and Bread:

The most common fruit clearly identifiable in these artefacts are apples. The apples are generally depicted in bowls, not on trees or pictured singly. Loaves of bread and coins are also common motifs. All three are believed to connote abundance, the provision of nourishment, wealth, “plenty”, and possibly offerings given to these goddesses as well as blessings received from them.

Apples are found as potent symbols throughout Germanic, Celtic and Roman mythology. In Greco-Roman mythology, the goddess Hera has an apple orchard which is tended by the Hesperides, the daughters of Atlas. There are either three, four or seven Hesperides who tend the apples, depending on the version of the story. These apples are said to grant immortality. Hera placed a hundred-headed dragon named Ladon to watch over the apples and protect them from being eaten. While this story was not considered as central to Roman mythology as it was in Greek (Hera was syncretized to Juno), the story was known. And in this story we see an image of at least three women tending apples guarded by a serpent/dragon, which is a very common visual motif found on Matronae altars.

Apples are found throughout Celtic mythology. The true home of Mannanan mac Lir, the principle sea deity and a trickster and ruler found throughout Irish written and oral lore, is said to be Emain Ablach (the fortress of apples). In Welsh and British mythology, particularly connected to Arthurian legend, there are stories of Ynys Afallach or Avalon, the Isle of Apples. Apples are often associated with immortality and abundance, and the wands of druids were said to have been made from either apple, oak, or yew wood. Apples feature in several well-known stories as well. (MacKillop, 1998)

As for Germanic mythology, it is Iðunn who tends the sacred apples. Iðunn’s apples of immortality keep the Aesir young and healthy. According to Hilda Ellis Davidson, she believes Iðunn was in possession of a bowl of apples as opposed to an orchard, and she cites the story in the Prose Edda where Loki gives her and her apples to the Jotun Thiazi, and then must steal her and her apples back. She claims that, since Loki is able to transform both her and her apples into a nut so he can carry her off, the apples must be in a movable form and are most likely a bowl of apples rather than a tree or a single apple (Davidson, 1990).

Flora:

Most altars have decorative flora carved throughout, especially along their sides and backs. Trees, particularly oak trees, are common on these altars. Frequently snakes are found wrapped around these trees.

There is mention the 8th century Vita Bonifatii auctore Willibaldi, that Anglo-Saxon missionary Saint Boniface and his men cut down a tremendous oak tree sacred to Donar in the region of Hesse, Germany. Oaks figure prominently throughout Celtic mythology and history as well. They were considered sacred to Druids, and the English word druid is derived in part from the root dru-, meaning oak (Mackillop, 1998). Oaks were also considered sacred to Jupiter.

Trees are often understood to symbolize a deity’s ability to travel between the worlds and exist in different realms, the roots planted in the chthonic realms and branches up in the celestial ones, with the trunk in the human world. This is important, because it speaks to both the importance of these goddesses as well as indicating a possible ability to influence the human realms, the divine realms, and the realms of the ancestors. Images of trees, especially trees with snakes, are found cross-culturally and are generally associated with the concept of the World Tree that holds up and connects multiple realms of existence (Garman, 2008). Again, there are stories found in Greco-Roman mythology about snakes or dragons guarding sacred trees. In Norse mythology, there is the story of Nidhogg, the serpent who gnaws on the roots of Yggdrasil, the world tree. And dragons were often found at the bottom of deep lakes or guarding trees in Celtic mythology (Mackillop, 1998).

Fauna:

The most common animals found on Matronae carvings include snakes, birds, sacrificial goats, and dogs. Snakes are found wrapped around trees, sometimes with ram horns or ram heads. The sacrificial goats are sometimes depicted with one head and three bodies, or one body and three heads. The five birds found on Matronae altars are ravens, doves, peacocks, geese, and cranes or storks. Dogs are found on some altars, and are often found on altars that also have images of boats (as we see with Nehalennia’s altars). Images of eggs and a random assortment of other small animals are sometimes also depicted, and are generally understood to represent fertility and fecundity (Garman, 2008).

There are five specific birds found in Matronae iconography: the dove, peacock, raven, goose, and crane or stork. Doves were associated with healing, love, peace and health and were sacred to Venus. Peacocks were sacred to Juno and associated with childbirth (Garman, 2008). Ravens and crows are found throughout Celtic and Germanic mythology, and in both cultures were associated with war, death, wisdom, and prophecy. Geese symbolized guardianship throughout the Romano-Celtic period, and both carvings and the remains of geese have been found at sacred sites throughout ancient Celtic territories. Cranes were associated with female power and transformation in Roman society (Garman, 2008). Cranes are found throughout Celtic mythology as well, and are often believed to have been transformed human women. The ancient Britons, according to Julius Caesar, would not eat cranes because of this belief. And representations of cranes appear in Celtic iconography as early as 800 BCE. Cranes were thought to be associated with healing (Mackillop, 1998).

Goats were generally depicted as sacrificial animals, and in Matronae altars are depicted in the process of being sacrificed. In Rome, goats were sacrificed in the spring, and were the preferred sacrifice for forest gods such as Faunus, Silvanus, and gods of the spring. They represented fertility and prosperity (Garman, 2008).

For Romans, snakes represented protection, healing, rebirth, and prophesy. Snakes wrapped around trees (as stated above) may have indicated the snake as guardian of sacred trees. Snakes represented renewal and immortality to many ancient people, due to a belief that the snake’s shedding of its skin was a type of rebirth. And the snake was believed to be able to traverse multiple realms, an indication strengthened by the image of a snake wrapped around a tree (Garman, 2008). Again, as trees were often depicted symbolically as connecting the lower, mid, and upper realms, a snake wound around a tree would be understood as being able to travel between these realms. The snakes are commonly depicted with ram heads or ram horns.

Rams were commonly associated with Mercury and with northern British war gods, possibly symbolizing sexual energy and aggression. One theory about the meaning of this image is that the combination of snakes with rams could symbolize the combination of fertility, sexual aggression and regeneration (Mackillop, 1998).

Dogs were associated in both Celtic and Greco-Roman cultures with healing, hunting, guardianship, companionship and death. Dog remains were found in ancient Celtic holy wells, and were associated with the Gaulish deity Sirona, British deity Nodons, and Nehalennia, a Matronae goddess with her own temples and individual cultus who was either Gaulish or Germanic. Dogs are mentioned throughout Celtic mythology, sometimes as benign beings, sometimes as frightening beings. In both Norse and Welsh mythology, monstrous dogs guard the land of the dead.

Boats are mostly depicted with images of Nehalennia, but are found in a few other Matronae artifacts as well. Nehalennia’s temples were found on the coast, and she is believed to have been a Matronae goddess specifically associated with ocean travel, trade, healing and protection. Boats are straightforward symbols in all three cultures of trade, prosperity, and travel. Boats are also associated in all three cultures with the dead, as there are stories found in all three cultures about the dead traveling across water in order to reach the underworld. In Norse mythology this is far less of a central theme than in Roman and Celtic mythology, though Loki is said to ride in a boat, alongside the rest of the Muspilli, made of the fingernails of dead men during Ragnarok. More Germanic evidence of the connection between boats and the dead is to be found in the ship burials common throughout the Germanic territories.

Spinning materials, particularly thread boxes and a distaff, are found in just a few Matronae and Matres carvings. But the fact that this image is found at all is significant, as both the Parcae in Roman mythology and the Norns in Norse mythology are depicted as three important women spinning and weaving the fate of humankind.

Diapers and menstrual pads are more commonly found in depictions of the Matres. The symbolism of this is straightforward, and would have been recognizable in all three cultures. When these items are depicted, the images are referencing motherhood, human fertility and reproduction.

Iconography specific to Rome:

Cornucopias, globes, and shell-shaped canopies were motifs specific to Roman art, and had specific meanings in the context of Roman culture. While these motifs would not have been found in indigenous Germanic or Celtic religion or culture, the meanings behind these symbols must have been important and applicable enough that artists consistently included these images in depictions of the Matronae. Cornucopias were associated with abundance, fertility and prosperity, and with river deities specifically. Globes were sacred to the Roman goddess Fortuna, and implied fate or fortune and the ability to change luck at a moment’s notice. The shell shaped canopy was associated with Venus and other Roman goddesses associated with water (Garman, 2008).

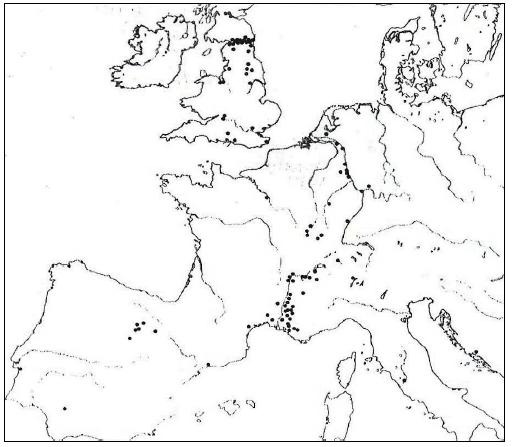

Left: Altar combining a representation and a dedication to the Matronae Aufaniae from Bonn (Germany). All three seated figures hold bowls of apples. Right: Pipe-clay group of three Mother Goddesses from Bonn wearing the typical round hat of Germanic goddesses, with bowls of apples in their laps. In Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn. LIMC, Suppl., vol. 8, 2, p. 553, n°1 and 4.

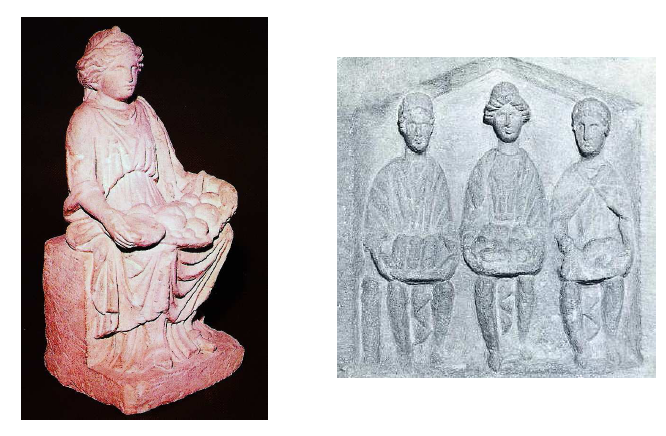

Left: Single Mother Goddess from Alésia (Côte d’Or). In the Musée Alésia. Deyts, 1998, n° 28, p. 67. Right: Plaque from Cirencester, Gloucestershire (GB), representing triple seated mothers of Classical type. In Corinium Museum, Cirencester.LIMC, Suppl., vol. 8, 2, p. 554, n°16. Again, note the bowls of fruit and bread in the laps of the seated figures, and the distinctive clothing styles.

Images from http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/getpart.php?id=lyon2.2009.beck_n&part=159103

Reference:

Beck, Par Noemie. Goddesses in Celtic Religion. Cult and Mythology: A Comparative Study of Ancient Ireland, Britain and Gaul. Doctoral Thesis: University College of Dublin, published December 4, 2009.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books, 1990.

Garman, Alex. The Cult of the Matronae in the Roman Rhineland: An Historical Evaluation of the Archaeological Evidence. Edwin Mellen Press, May 2008.

Irby-Massie, G.L. Military Religion in Roman Britain. Brill, 1999.

Mackillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Tacitus. Agrigola & Germania. Trans: H. Mattingly, Penguin Press, 2010.