I recently had the honor of presenting a devotional and oracular ritual dedicated to the Matronae at the Many Gods West conference held in Olympia, WA. The Matronae are a collective of indigenous Germanic and Celtic goddesses who were worshipped syncretically in the Roman Empire. It was a blessing and a gift for me to be able to present this ritual along with Rynn Fox and a fantastic team of warders and ritual helpers. I love these goddesses very much, and because they are not very well known, I wasn’t sure how much interest there would be in such a ritual. But we had a wonderful turnout, and I have received many questions since the ritual. I will be posting a series of articles about the Matronae in the hopes of addressing some of the questions about who they are.

Important things to Note when Discussing the Matronae:

The biggest challenge with discussing the Matronae is the scarcity of surviving information about them. All that we know about the Matronae are from archaeological finds. There are, however, over 1100 surviving inscribed plaques, altars, and statues, and several temple sites, scattered across Europe. These inscriptions name them as Matronae and/or as Matres, and in a few places there are inscriptions to goddesses called the Nutrices as well who share the same iconography and many of the same epithets. There is no intact surviving mythology about them, there is no information written by contemporary writers of their time period about them, their cultus, nor their worshippers. So to talk about the Matronae and Matres, we need to start with a discussion of their context and their inscribed altars and temples.

When looking at the cult of the Matronae and Matres, it is important to understand that “pan-European” universal paganism never existed – there was never a single unifying set of religious beliefs nor pantheon that spanned all of Europe. There wasn’t even necessarily a “pan-Germanic” or a “pan-Celtic/Gaulish” paganism. Every individual tribe had their own pantheons, with their own stories, rituals and worship styles, and their own individual deities that may not have been found in the next tribe over. Even the more popular or larger, better known deities who may have been found in a number of different tribes may have had different divine relationships, different attributes, or different roles in the pantheon from tribe to tribe (which is why in some Germanic tribes, Odin was the head deity in the pantheon, in other tribes it was Freyr, in others Tyr, and in others Thor). These regional distinctions are important to note, because the Matronae and Matres were a collective of many deities, each one specific, regional, local, and distinct. Each individual goddess had her tribe, her land feature, her individual relationships with others from her specific pantheon etc. Each goddess was a unique, standalone goddess. The Matronae functioned as a collective of individual goddesses, each of whom had their own separate stories, attributes and even pantheons. The individual goddesses crossed regional and tribal lines to function as a multi-cultural, multi-regional, and multi-traditional collective.

We do know for certain that the Matronae and Matres must have been very well loved, and were worshipped extensively throughout the Roman Empire. There remain over 1100 surviving inscribed plaques and altars, and several large temple sites surviving from the 1st – 5th century CE. Each inscription follows a specific formula – the altars were dedicated in gratitude for answered prayers. These surviving votive remains are mostly high quality plaques and elaborate temples and altars; each one would have been expensive and time consuming to have had made, and each would have been made by a professional artist. There may be many more surviving altars and votive items, however not all have survived in clear enough fashion to be able to be included in the count. All 1100 include an inscription clearly stating something like, Person x dedicates this altar to the Matronae and/or Matres in fulfilment of a vow for a prayer answered, which is how we know the altar is a Matronae altar – the inscription literally says so. There are many other surviving carvings that include three female figures and many of the associated iconography, but either there was no inscription or the inscription was damaged beyond recognition (Shaw, 41). This also means that for each surviving inscribed altar, someone had a significant and major prayer answered, and had an inscribed altar made in gratitude for their prayer being granted. In other words, we have hard evidence of over 1100 definitively answered prayers over a roughly 500 year period of time.

Matronae: History and Region

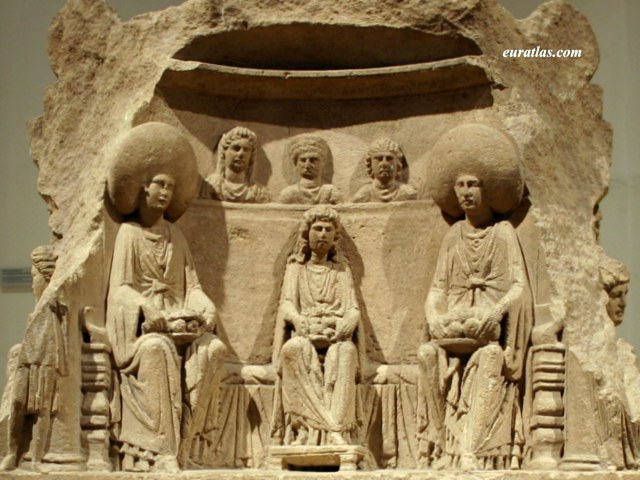

The Matronae, as they appeared in the Roman Empire, were worshipped from the 1st-5th centuries AD. We know this from carbon dating of surviving inscriptions and from dates written on some of the inscriptions. The earliest inscriptions that may pre-date the Roman Matronae cultus are written in Gaulish and located in Southern France, and may be as old as 1st-3rd centuries BCE (Beck, 40-42). These early Gaulish inscriptions were just inscriptions and did not also include images. The majority of the surviving plaques and altars are dated from after the Roman Empire had conquered many Germanic and Gaulish tribes. These altars almost always include an image of three seated women wearing the traditional (and distinctive) clothing styles of a Germanic tribe called the Ubii (Garman, 7). These outfits include exaggeratedly large linen bonnets and crescent or half moon shaped pendants.

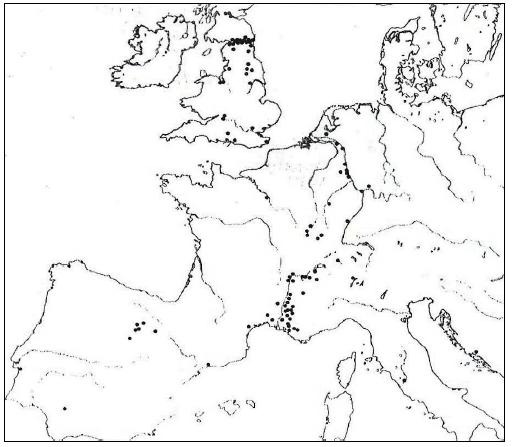

Altars to the Matronae, Matres and Nutrices have been found all throughout Europe, from the Iberian peninsula to Northern Italy to Algeria. The vast majority of the altars were located all along the Rhine river, with a handful found along Hadrian’s Wall in Great Britain (Garman, 16-17). If Nehalennia is understood to be a Matronae goddess as well, there are also several temples found to her in the Netherlands. The altars found along Hadrian’s Wall are believed to have been brought there by soldiers from the lower Rhine region who were stationed there (Shaw, 43). And statues depicting the “nutrices”, who share common iconography and epithets, have been found in Slovenia and North Africa (Beck, 73).

Map showing the distribution of the dedications to the Matronae with and without epithets. ). A. Matronae with epithets. B. Matronae without epithets. Derks, 1998, p. 129, fig. 3.19 (after Rüger, 1987, fig. 1 and fig. 2). Maps from Beck’s thesis paper.

No one is sure where the concept of a mother goddess collective originated. The earliest inscriptions are found in Gaul, indicating the possibility that the whole concept of worshipping divine mothers as a group in this manner may have been a Gaulish or possibly a Greek religious concept originally. There are several inscriptions to the “Matrebo” written in Gaulish using the Greek alphabet dated to the 1st-3rd century BCE that follow a similar inscription formula: “in gratitude on the accomplishment of a vow” (Beck, 40).

The female figures found on the Matronae altars however are understood to be dressed specifically and uniformly in Ubii clothing. The Ubii were a Germanic tribe who chose to make early and strong alliances with Rome rather than waiting to be conquered. They were originally from east of the Rhine river but were moved into a depopulated area on the west bank of the Rhine river. The modern city of Cologne was the Ubii capital (Garman, 8). The Ubii were one of the few civitates to be granted the status of foederatae, which gave them the unique status of having all of the rights of a Latin colony. They were extensively Romanized, and Romanized early as compared to other conquered and annexed tribes (Garman, 10). The majority of Matronae inscriptions are found along the Rhine river, in areas that were specifically Ubii territory (Garman, 8). It is possible, therefore, that the Matronae cult may have been originally an Ubii religious movement or idea that took on Roman iconography and attributes.

So that should give folks a sense of the history, time and locations from where the Matronae and Matres originate, and some of the complexity of understanding who and what they were (and were not). Stay tuned for more Matronae information!

Reference:

Beck, Par Noemie. Goddesses in Celtic Religion. Cult and Mythology: A Comparative Study of Ancient Ireland, Britain and Gaul. Doctoral Thesis: University College of Dublin, published December 4, 2009.

Garman, Alex. The Cult of the Matronae in the Roman Rhineland: An Historical Evaluation of the Archaeological Evidence. Edwin Mellen Press, May 2008.

Shaw, Philip. Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World: Eostre, Hreda and the Cult of Matrons. Bristol Classical Press, September 2011.

I’m very curious how much the patterns match the reverence of the Disir associated with holy days further North.

It seems like a holiday like Mothers’ Night (Modranacht) can just as easily be for a group of motherly Ancestors or motherly Divinities…

–Ember–

Great article, thank you! 🙂