This isn’t the column that I intended to write today. I wanted to continue my theology series but for weeks now I have been doubled over with grief and anger and a tremendous feeling of helplessness as I watch the future of our world crumbling away. I suppose it’s the downside of being a diviner: I am capable of seeing all the various possibilities and potentialities when I watch the news; I can see multiple futures unfolding and none of them good and sometimes it’s very, very difficult to turn that awareness off. Since August 18 when Daesh slaughtered the custodian of Palmyra Khaled al Asaad, and then shortly after bombed the temple of Ba’al Shamin, I’ve been fixated on this, sickened. Yesterday I learned that this filth had likewise bombed the Temple of Bel and…Palmyra is effectively gone.

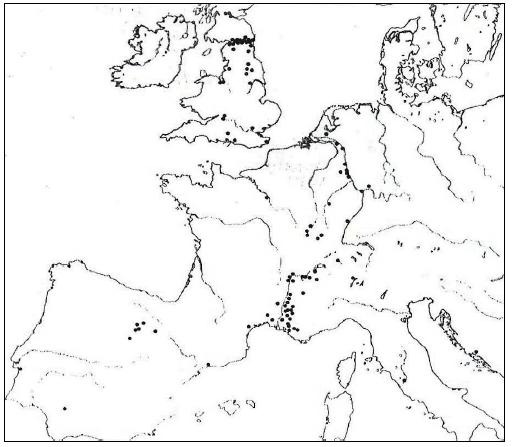

The editor of polytheist.com has been doing a series #ThisIsWhyWeNeedPolytheism and that is the thing that most inspired this article, because we do, desperately. We as polytheists represent pretty much everything these pig-fuckers are against, so much so that the very memory of cultus is a threat to their desired state of being. Why? Because as long as one temple is left standing, as long as these sacred places remain alive in living memory there is a physical testament to the fact that things were not always as they are now. We did not always live under the yoke and threatened domination of monotheism. The people of the lands Daesh has conquered, did not always bow their heads to Allah alone, and did not live in fear of torture, slavery, and worse. Once, things were very, very different for their ancestors and so long as even one temple stands, there exists a signifier that in the future, things can be different again.

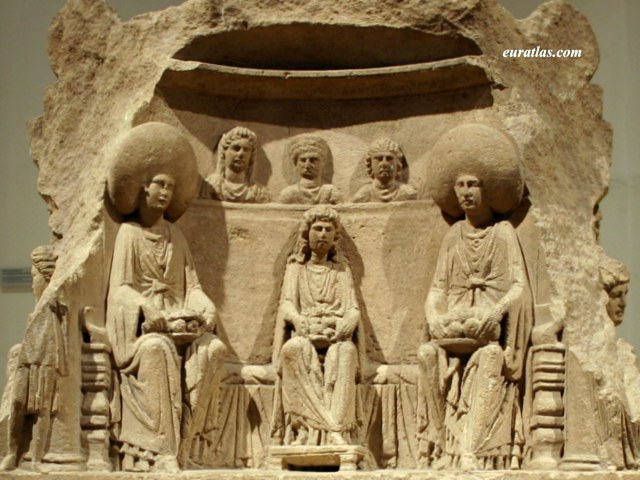

These spaces that they so diligently destroy, after plundering and mining them for treasure, represent the potential for a very different, better future and stand as stark reminders that the legitimacy of their claim to the lands they inhabit is tenuous at best. We are horrified, and rightly so, by the human rights violations this filth commits, but we should be equally horrified, if not more so, by the destruction of ancient spaces and places of worship. The destruction of a place like Palmyra, isn’t just the destruction of an ancient building, it’s an attack on the future and what it might be, what it can become. It’s a severing of any link with a pre-Islamic past, and likewise a severing of possibilities for the future. In blowing up the Temple of Ba’al Shamin and the Temple of Bel, they’re damning future generations and that is an attack far more long lasting in its impact, than simply the loss, however grievous it might be, of an antique site.

I made the mistake last night of reading a number of different news articles about this, something that left me unfit for human contact for a few hours. My partner had to pretty much order me off the computer (he set me to watching cat videos for a half hour, because I was shaking and so upset). You know what I fear the most? We’re in WWIII and it’s a war unlike any that we’ve fought before. In WWII we got very, very lucky. We had the leaders we needed to protect and defend: Churchill, Roosevelt, Eisenhower, …even Stalin (he was worse than Hitler in some ways, but he was able to hold the line against the Germans in a way that Nicholas II never, ever would have been able to do), and of course generals like Patton. This time, we’re not so lucky. Across the board we have petty, untried leaders seemingly incapable of taking the long term view. None of them seem to be able to see the long term consequences of their actions and in-actions…except perhaps (horrifyingly) Putin.

Daesh is moving north and they have already made threats against Egypt and India. How long until they start attacking Europe? What then? We can hope that our governments have strategic plans for halting their progress, and maybe they do, but exactly how effective have they been up to now? Actually, attacks on Europe have already happened–by individual gunmen “inspired” by this group but attacks nonetheless–and we seem incapable of rooting potential perpetrators out. What exactly are we going to do when it’s our ossuaries and our sacred places, and the land worked by our ancestors under attack? Will we then perhaps take it a bit more seriously?

I salute the work of fighter Abu Azrael in what may well become a ‘by any means necessary’ war. It does not answer my own feelings of impotence however. What can we as polytheists here do? This is a polytheist problem as much as it is a human rights problem. The most recent article at The Wild Hunt should have brought that powerfully home. Polytheists today are dying, and worse.

For those of us positioned in ways that do not allow for the taking up of arms, for the wading into fighting, for the shedding of the blood of our enemies, what can we do? I don’t have any answers there. I have no doubt that in time the Gods will have their vengeance. It is the way of things and it is good and holy. But that does nothing to alleviate our helplessness now in the face of political incompetence (personally I think our government needs to stop kissing the collective asses of Riyadh and Jerusalem for starters). What can we as polytheists do?

Well, I’m going to throw out some ideas here, because Daesh isn’t our only threat. I very firmly believe that the fundamentalism and inherent lack of intellect, dignity, and respect that drives the atrocities of a group of Daesh, is not in any way inherently different from what drives our own, homegrown, Christian evangelical/fundamentalists. The latter group may not be militarized….yet…but it is not an inconceivable future, particularly given the insidious infiltration of fundamentalist Christianity into our armed forces. While we struggle to cope with horror after horror in the Middle East, I think it very important that we not turn a blind, forgetful eye to the potential danger right here at home.

This is one of the reasons why it’s so important to be politically aware. Read – and not just American papers/news sites. Any country that considers Fox News a reliable news source is not a country that can be trusted with the educational welfare of its citizens. Educate yourself. Read as much as you can, from as many sources as you can (perhaps most especially those with whom you disagree. It’s always good to gain insight into the opposing position).

Vote. This is especially important for women – our foremothers were tortured, beaten, imprisoned, and worse to gain for us the right to vote. Use it and not just in presidential elections. The real power isn’t at the top. Those local elections matter. This is something that Christian fundamentalists have understood for a very long time: local elections, especially school board elections matter in ways that I think few of us realize. Get involved up to and including running for office yourself, (if you have the temperament, education, and aren’t a total asshole).

Know who your senators and congressmen are and what their positions on various issues are as well. Know who our ambassador to the United Nations is. Don’t be afraid to contact these people. They work, whether they realize it or not, for us. Write your letters, sign your petitions, and show up at rallies. Make your voice heard. Take it to the streets if you need to and definitely take it to the polls. Challenge everything. We can’t afford to blind ourselves to what’s going on around us. I often grow very irritated when I will post something on facebook about Palmyra or the abuse of women or Christian abuse and someone will say “that makes me sad.” Does it? So what? What are you going to DO about it? That’s what it comes down to: What are you going to do?

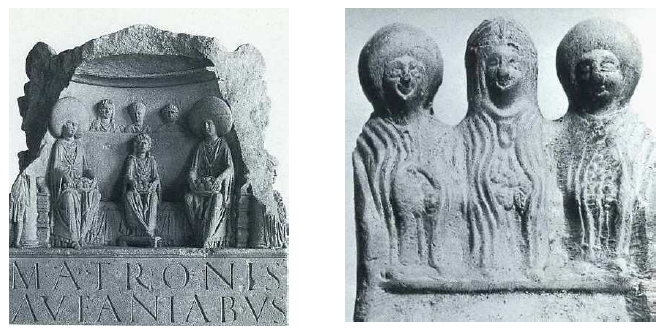

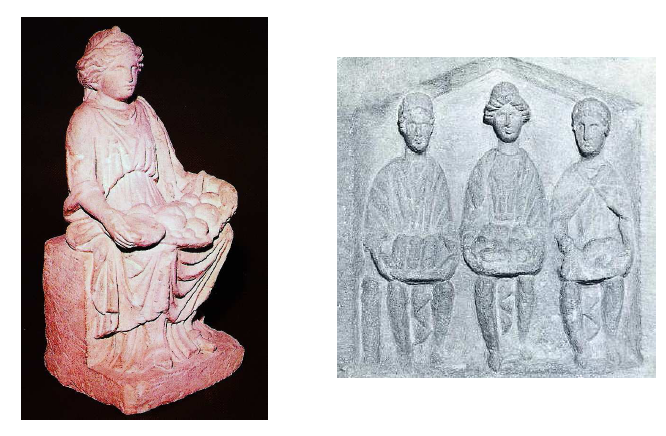

Then there is the religious response. What can we do there? We can pray, which seems like such a passive response. It isn’t, but it seems so all too often. We can curse and hope that the Gods lend Their power to our workings. But there’s a third thing we can do as well: we can show our devotion to the Gods whose places were plundered. In this, it doesn’t matter what type of polytheist one is, whether one is a Heathen or Canaanite, Greek, or Kemetic polytheist. For every sacred place razed, we can pour out visible devotion to those Gods. For Ba’al Shamin, for Bel, and many more (a list of many of the places vandalized and destroyed by Daesh may be found here) let us set up personal shrines, create art (thank you, Tess Dawson for this idea), write prayers, pour out offerings. We can choose to allow this blind destruction to spur the rebirth of Their cultus. We can choose to allow this to bring active veneration by the hundreds and thousands back into our world, renewed, refreshed, and fierce. These are no longer just the Gods of Canaan; They are the Gods of every polytheist living today. Their own people may have abandoned Them. Usurpers may be destroying Their sacred sites, but They are still great and good immortal Gods and we can still pay Them cultus.

In response to this destruction, we can foment a polytheist renaissance for these Gods and all of our own. That’s the way that I choose to respond though a large part of me would very much like to be locked to my gun wading through bodies in Syria. That is not possible but this type of response is. Moreover, we can commit ourselves to the restoration of all of our traditions again and again and again. To quote Tess Dawson:

“We need to nourish, hold, and maintain our polytheist spaces, our holy places, our sacred discourses, our necessary conversations, our holidays, our rites, our offerings, our blessed gatherings. We need to nourish, hold, and maintain these things on behalf of our deities, our ancestors, and each other. And we need to do this far more than any curse or call for vengeance. Indeed, these very acts themselves are revolutionary and the very things that Daesh and others would try to blot out. Do these things first, and then, only then, contemplate curses because vengeance is nothing when there is nothing left to avenge.”

I would only add that it is not something to be done instead of cursing, but in addition to and perhaps first. Let us be like the hydra of ancient Greek lore: every time one of our sacred sites is destroyed, a dozen more avenues and places of devotion spring up. That is particularly fitting response, in my opinion.

We need polytheism today, more than most people realize. Why? Because the underlying cause of so much of the inequalities and aggressions that we see and fight every day are rooted in monotheistic hegemonic insanity. This is what gave us the Doctrine of Discovery (look it up!), colonialism, misogyny and these things bred racism and classism and so many of the other evils that eat away at humanity and hope. We had conquest in the polytheist world, but not the peculiar type of fundamentalism that so defines our religious world today. Freud speculated that such religious intolerance had its birth with monotheism and I concur, and we were all raised surrounded and inculcated with that poison. Until that changes, we’re pissing in the wind because our minds and motivations will still be poisoned. The solution: change ourselves. Work to clean out our own minds and spirits, to root ourselves anew every day in our traditions, to know that there are some lines that we should never, ever allow to be crossed.

The terrible soul-wrenching destruction that almost daily we can read Daesh is causing can inspire us to do this work more fully, starting with ourselves. It can make us better polytheists more deeply, passionately engaged with our Gods and with our world. We can dedicate ourselves to an accumulation of small acts, to changing the world around us day by day, minute by minute. I do not know of many other tools available to us, than a stubborn determination not to give up on our world.

There’s a wonderful quote from the Talmud that a friend of mine shared with me years and years ago. I saw it again recently making the rounds on social media. It was a timely coincidence. This quote holds wisdom that has sustained me through very difficult years and deep exhaustion with the Work. I share it with you now, because with all the horror that we read about day by day, it’s painfully easy to fall into compassion fatigue, depression, and despair:

“Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. You are not expected to complete the work, but neither are you permitted to abandon it.”

So we persevere, and maybe, just maybe, in the end it will be enough.

A few good links: