by Ryan Smith

Reality in pre-Christian Scandinavian lore is not fixed, unchanging, or static. Much like life and the natural world all things go through cycles of growth, change, and eventual decline and demise. As is described in the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda in the beginning was the Ginnungagap, a great void with the fires of Muspelheim on one side and the ice of Niflheim on the other. One day the fire and ice rose up and collided in the gap, creating a great cloud of steam from which emerges Ymir and the great cow Audumla. Ymir sired the frost giants with all living in a land of frost for an indeterminate amount of time. One day Odin, Vili, and Ve, the grandsons of Buri and an unknown frost giant, rose up against Ymir, slew it, and in conjunction with all the Gods used its body to create Midgard. At some point in the future the giants of Muspelheim, led by Surtr, will rise up, slay the Gods, and burn the Nine Worlds after a new world will emerge from the ashes.

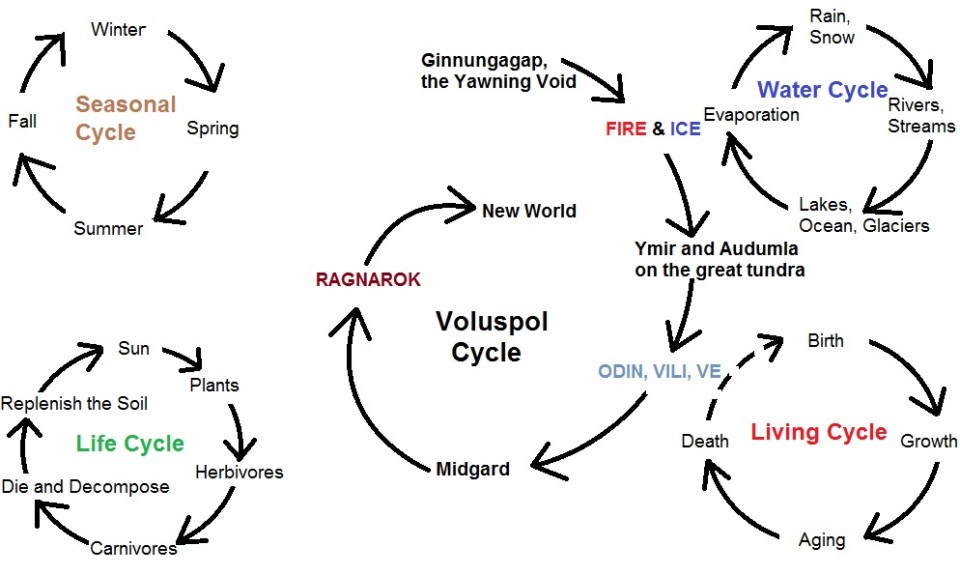

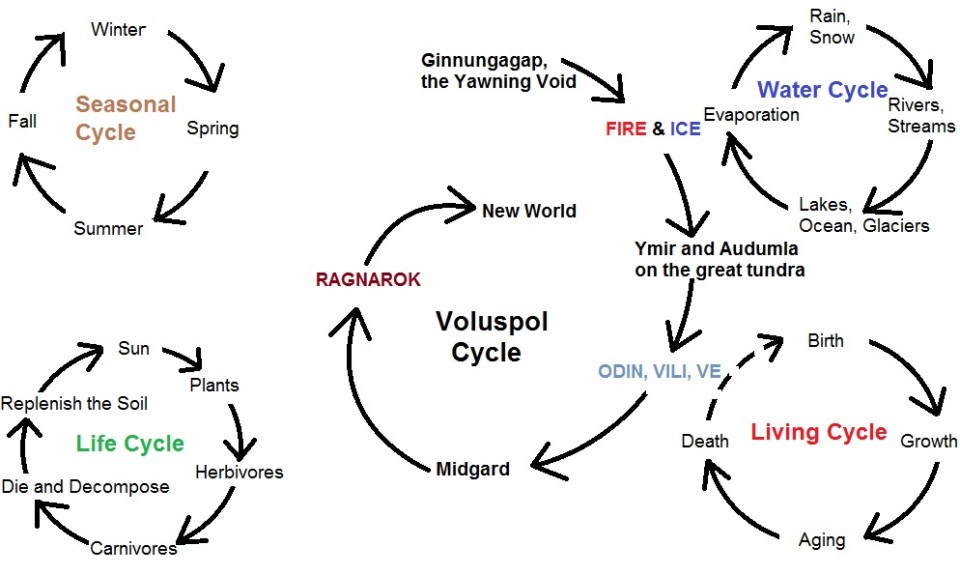

The cyclical pattern is very consistent throughout the lore. At the beginning of each part of the cycle there is an established reality: the Ginnungagap, Ymir and the land of frost, and Midgard. Each of these arrangements of reality grow, change, and come to an end through deliberate action bringing about cataclysmic transformation whether this is in the form of the collision of fire and ice, Odin’s uprising against Ymir, or Ragnarok. These reality-shaping events are followed by a new world created from the elements and components of the old. This cosmic cycle can be summed up in three stages:

Established Reality

The present order of the cosmos as best known. This is seemingly fixed, unchanging, and permanent to those who exist within known reality.

Cataclysmic Upheaval

Reality is torn asunder by events of cosmic proportions.

Reconstitution and Reconfiguration of Reality

The survivors of the cataclysm use the components, elements, and foundations of the old order to construct a new form of reality. This reality is one that is more beneficial to those who craft it as they create the conditions necessary to thrive.

The flow of this cycle is summed in the chart below:

Also shown are other cycles observed in nature. In each case a similar pattern of new forms transformed from the elements of the old is present. The life cycle is an excellent example of the same concept at work. Plants, fed and energized by the light of the sun, grow and feed herbivores. These herbivores become prey to carnivores who eventually die. When the carnivores die their bodies break down to their core components, enriching the soil enabling the growth of new plant life thus ensuring the cycle continues. The seasons follow a similar march from the cold of winter to the promise of spring, the bounty of summer, and the retreat and preparations of autumn for the coming winter. Water, in turn, pours from the sky as rain and snow, runs across the land in rivers and streams feeding lakes, oceans, and glaciers before evaporating and returning to the atmosphere. Even in the case of the cycle of living, beginning with birth and ending with death, those who reach the end of their individual cycles contribute directly and indirectly to the lives of those who follow them. Whether through reproduction or the influence of their actions on the world all that lives plays a critical role in shaping the lives of those who follow.

The progression of events and worlds in the Voluspa follows similar logic to the cycles of life. The end of each world does not herald, as it does in the Abrahamic tradition, the end of reality. Each reality dies and its components, catalyzed by the upheaval that brought their demise, are reformed into a new reality. The demise of one world gives rise to a new one with the universe continuing on much like the natural cycles. This cycle is mirrored in the creation of humans who were made from two dead pieces of driftwood. Just as the Gods made Midgard from pre-existing materials they fashioned the first two humans from existing materials, giving unto them the gifts of heat, breath, and intellect. Nothing comes from nothing in Heathen cosmology as all things obey these fundamental dynamics.

A cyclical understanding of the universe is distinct from the more linear, mechanistic view which prevails in society thanks to Abrahamic influence. Reality, whether by the Big Bang or act of God, comes into existence with set rules and boundaries. If and when it ends that end is it. In such linear views of reality everything is arranged like some vast book with a clear beginning, end, and narrative describing how one gets from one to the other. This imposes a top-down, dominating understanding of the world where the ideas and opinions in line with this narrative are the only ones worthy of consideration and all others are secondary at best. It is an ideal perspective for asserting singular truths and monopolies on information at the cost of constricting discourse, discussion, and debate.

This cyclical understanding of the universe approaches reality from a different perspective. When one thing dies, breaks down, or falls apart its constituent elements and components go back into the world to facilitate new life and new creations. Even if a person or an animal dies without siring offspring they contribute to new life both literally, in the form of their decomposing body, and abstractly through the wisdom gained from their experiences, the fruits of their labor, and the impact their deeds had on the world around them. Just as the seasons progress so do lives, societies, and the universe. These broad strokes are consistent even as the details vary.

Another crucial element of Heathen cosmology is the relationship between the Gods and the universe. Unlike Abrahamic tradition, where God is present in all of creation while also being transcendent and outside of it, the Gods exist within the same reality as us and are not above or outside of it. While They engage in a great act of creation when shaping Midgard this is done within the context already established patterns and principles. Reality is not willed into existence ex nihilo but created from existing components. They also do not create the whole of the universe. When or where the Yggdrasil came from is not known and only Midgard and Asgard are mentioned as creations of the Gods in the lore. Even with all Their preparations, might, and wisdom the Gods cannot totally avert the inevitability of Ragnarok and Their own demise. They are a part of the same reality as the rest of us and, like everything else, are bound to its cycles.

What this suggests for Heathens is very profound. If, as the lore shows, reality is the result of endless moving cycles and great upheaval and transformation then we must consider how we live with a similar understanding. When the world and how it is organized is not permanent but can be changed through action this suggests the same is true for our lives, society, and the world around us. The main constants in such a conception of reality are transformation, interaction, and webs of relationship.

This poses a serious question to Heathens and adherents of such an understanding of reality. If all things can be changed through deliberate action one must ask what needs to be changed and what should be preserved. One of the main themes of the coming of Ragnarok is the struggle of the Gods, especially Odin, to delay the destruction of the Nine Worlds in Surtr’s flames. Their actions to maintain the order of reality as it currently is, on the grand scale, suggest there are certain conditions and arrangements worth preserving. Supplementing this are the actions of Odin, Vili, and Ve in ending the order dominated by Ymir and its offspring to pave the way for Midgard.

This dynamic, when taken in the context of other statements in the Havamal, give a clear sense of what should be maintained and what should be changed. The custom of hospitality, as illustrated in multiple verses in the Havamal, calls for aiding those who come in need regardless of who they are as best illustrated in this verse:

“Curse not thy guest, nor show him thy gate,

Deal well with a person in want.”

Havamal 135

Equally potent is the reminder of the despair those in a state of poverty and deprivation feel:

“Better a house, though a hut it be,

A man is master at home;

His heart is bleeding whose needs must beg

When food he fain would have.”

Havamal 37

Greed and cowardice are condemned as fiercely as generosity is praised:

“The lives of the brave and noble are best,

Sorrows they seldom feed;

But the coward fear of all things feels,

And not gladly the greedy gives.”

Havamal 48

This verse is an especially potent example with its assertion that those who are brave and noble, in turn, do not feed sorrow. In turn is the reminder that all find joy in life in one way or another and how important this is:

“All wretched is no one, though never so sick;

Some from their children have joy,

Some win it from kinsmen, and some from their wealth,

And some from worthy works.”

Havamal 69

These verses are paired with reminders to confront problems directly and resolve them rather than hoping they will fix themselves by leaving them be:

“The sluggard believes they shall live forever

If the fight they face not;

But age shall not grant them the gift of peace,

Though spears may spare their life.”

Havamal 16

This point is made even more potently in a later verse:

“If evil you see and evil you know

Speak out against it and give your enemies no peace.”

Havamal 127

One of the most direct reminders is the speech given by Beowulf in the famous Anglo-Saxon saga giving his reasons for voyaging to King Hrothgar’s hall:

“Then news of Grendel, hard to ignore, reached me at home: sailors brought stories of the plight you suffer in this legendary hall, how it lies deserted, empty and useless once the evening light hides itself under heaven’s dome. So every elder and experienced councilman among my people supported my resolve to come here to you, King Hrothgar, because all knew of my awesome strength.”

What motivates him, according to his speech, is hearing of the plight of Hrothgar’s people. Nowhere does he demand or show expectation of compensation, only asking for the chance to fight Grendel on his own terms.

What is clear is that which is beneficial to life is worthy of preservation and support. That which is harmful, stifling, or causes suffering must be replaced with new arrangements that are nurturing, supportive, and beneficial to as many as possible.

Those who perpetuate arrangements that cause harm must be opposed and neutralized by the most effective means for creating a new, better reality for all. The massive orgy of destruction and death preceding Ragnarok, as described in the Voluspa, offers a grim contrast with the first sign given by the Seeress being the total breakdown of society as humanity destroys itself:

“Brothers shall fight and fell each other,

And sisters’ sons shall kinship stain;

Hard it is on earth, with mighty abandon;

Axe-time, sword-time, shields are sundered,

Wind-time, wolf-time, ere the world falls;

Nor ever shall humans each other spare.”

Voluspa 45

Just as positive change is achieved through deliberate action so too is negative, detrimental change realized.

As has been shown in the cycles of reality change occurs because of action. All things eventually fade, age, and pass on but their replacement by newer forms is only possible through deeds, not waiting for the inevitable to happen on its own. The yawning gap was only replaced through the surging of fire and ice. Ymir’s waste was only replaced by Midgard through Odin, Vili, and Ve’s heroic uprising. Midgard and the Nine Worlds, in turn, will be replaced by the world yet to come because of the actions of the followers of Surtr, other Jotnar, and Odin’s plans and deeds in preparation for the final day.

Deeds drive the worlds, transform them, and make it possible for life to become better. It is also possible, as shown by Rangarok, for deeds to ruin them. The question we are left with is what should be changed, what should be preserved, and how to best ensure the most beneficial order for as many lives as possible.

About the Author:

Ryan Smith is a practicing Heathen sworn to Odin living in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is a co-founder of Heathens United Against Racism and a founding member of the Golden Gate Kindred. He recently finished his Masters in History, specializing in economic history, the modern Middle East, and maritime history, and currently works as an outdoor educator.