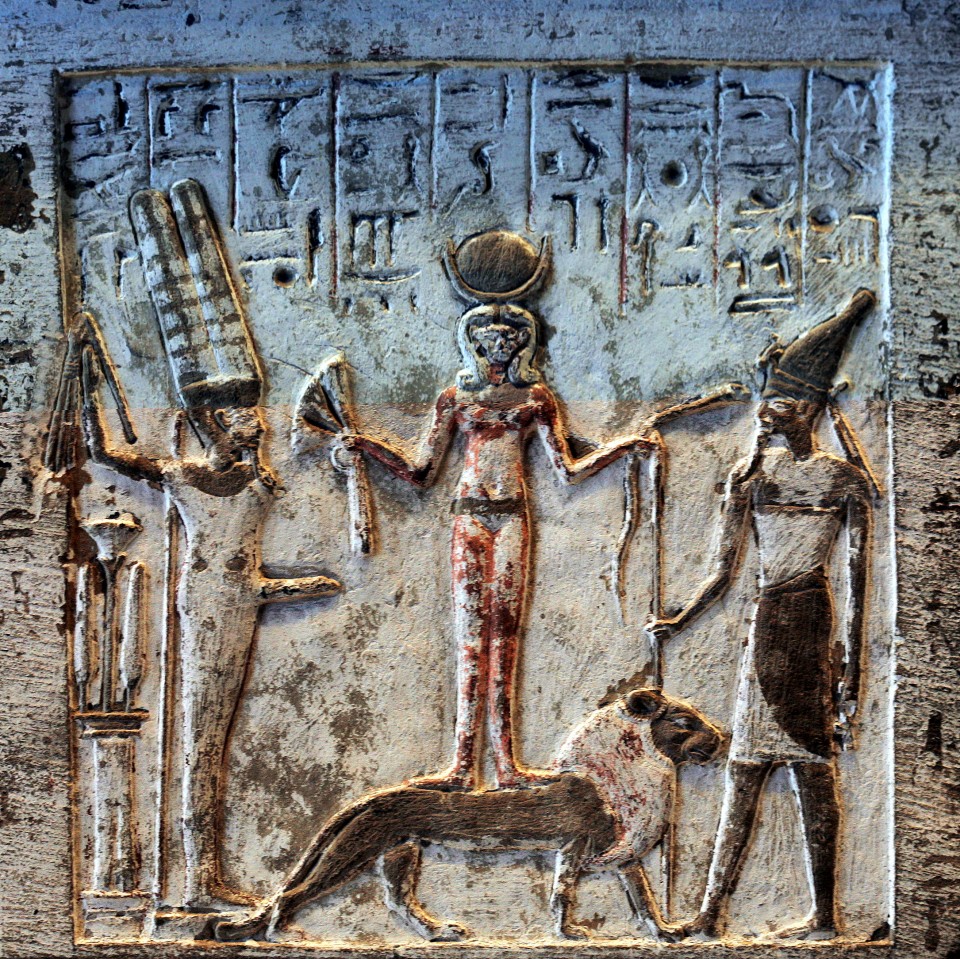

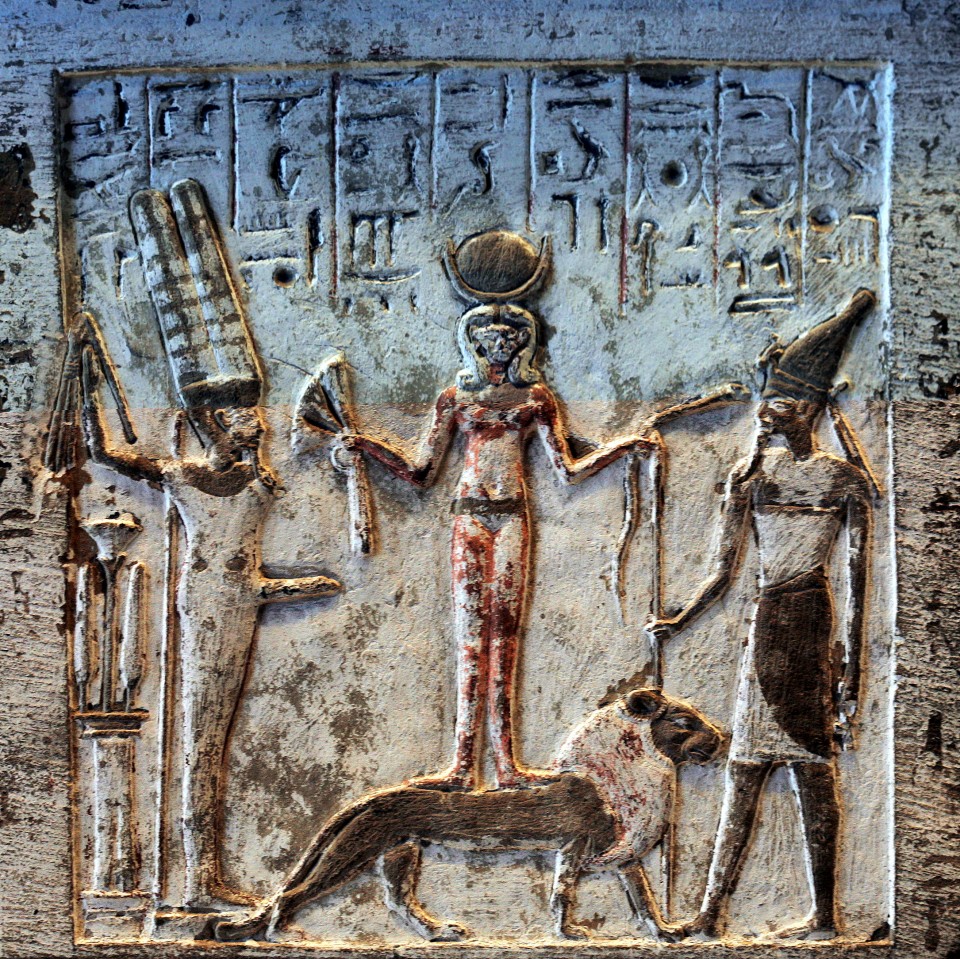

Image Credits: Photograph by Rama, used under Creative Commons License. Egyptian Stele Depicting Min, Qudshu, and Rashap, circa 1295-1069 BCE, in collection at the Louvre. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Resheph#/media/File:Stele_of_Qadesh_upper-frame.jpg

There has been a matter on my mind for a long time; a grievance that has long needed addressing and it’s been one that to my knowledge no one has touched. Before I get to that, I would like to talk about a holy image, displayed above, which holds many layers of meaning, many depths, many mysteries and Mysteries. Words do not wrap well around the splendors in this image and it is an image that crosses at least two pantheons.

There are a few versions of this Egyptian-made image but the image has three Beings in common, the Egyptian god Min or Amun-Min, the Canaanite and Egyptian god Rashap, and the Syrian goddess Qudshu. The particular version of the image I am looking at is currently housed in the Louvre, and this one is dated to about 3310-3084 years ago (1295-1069 BCE). It is a bas relief incised, carved, and painted on limestone.

The image so bursts with symbolism it is difficult to know where to begin describing it, so I will start the same way I read English, from left to right. The figure standing on the left is the Egyptian god Min or Amun-Min. He wears a tall two-feathered crown with a long ribbon trailing from it, he carries a flail in his right hand. He has a very pronounced phallus. Next is the Syrian goddess Qudshu. She stands on a lion, and she wears a horn-and-disk crown. She holds lotuses to the figure on her right (Min) and she holds a serpent to the figure on her left (Rashap). The figure to the right of the field-of-view is the Canaanite and Egyptian god Rashap. Rashap wears a tall crown with a tiny gazelle head on it. He holds a spear in his right hand, facing Qudshu, and he holds an ankh in his left hand. Rashap is especially notable in this image because, unlike most of his other images in Egypt, he is not in an aggressive warlike stance in this image.

In the most simplistic and basic descriptions possible, Min is a god of sexuality, fertility, potency, and abundance. Qudshu holds within her influence–because of her associations with ‘Anatu and ‘Athtartu–femininity, potential, sexuality, warriorhood, and transitional states. Rashap is a god of war, plague, healing, and protection. Min, a god of sexuality, procreation, and the powers of life holds in his hand a flail representing strength, force, and authority—a symbol of kingship and of the kings’ power, but he also bears the life-creating phallus. As Min holds the fertile Nile-watered lands of Egypt, Rashap’s reign is over the dusty desert lands, the wild dry hinterlands where few things grow. With the flail and the phallus, Min is in a position to ensure the protection, keeping, and proliferation of the kingdom. Rashap, by contrast, carries a weapon, acting as a guard in this image, and in the other hand he holds the key to life, an ankh. With the spear and the ankh, Rashap is a position to ensure the protection, keeping, and wellbeing of the kingdom—his situation is different from Min’s situation, but the goals are similar, and both teeter precariously in balance with Qudshu acting as fulcrum.

Qudshu stands between them on the back of a mighty lion who is tranquil at the moment. She is balanced very carefully on that fierce lion, and poised between these forces of life and death, abundance and restriction. In one hand lifted towards Min, she presents lotuses of beauty, of life and a fading of life, of impermanence, and of renewal, and of sweet breath and perfume. In the other hand, towards Rashap, she holds a serpent, which symbolizes protection, holding-together, threat and protection from threat, death, rebirth, and renewal. Both the lotuses and the serpent in their own ways represent changing states; life and death, rebirth and renewal, permanence and impermanence, boundless and bounded, the temporary and the eternal, the ever-flowing and the restricted.

This is just a small, small exploration of these many symbols and their meanings that this image encompasses—it is literally impossible to explain all of the depths of meaning, interpretations, and mysteries in this image. It is a holy image representing the careful balance of powerful forces held in check, one to the other, both ever-present, ever-necessary, in this world simultaneously. It is an image which is deeply sacred and meaningful, and I hold it in reverence even as the ones who created it viewed it in reverence as something sacred and meaningful. It is an image that if altered suffers a loss of meaning, of depth, of symbolism. If there is stuff added or changed, then the message is more difficult to read and is rendered less meaningful. It is like a sacred sigil calling forth the careful razor’s-edge balance of these beings and their mastery of these potent forces which cause things to function within parameters most beneficial for humanity. Sigils, for those who practice magic, do not function the same when they are altered. An alteration to this image is also like changing several letters in a word: it is a misspelling which causes a misreading and therefore a miscommunication. This holy image also does not function the same when it is altered and it would not carry the same message or hold the same space.

If someone wants to appear to other people as having respect for Christianity, that person will not typically make fun of communion in front of a Christian who is taking communion. If someone wants to make good with their Muslim neighbors, that person will not burn a copy of the Quran in the yard. Making lewd gestures at a Shinto shrine is also not the best way to start a dignified dialogue. So, when a person claims that he is being respectful about other religions and respectful about the deities, and respectful of the people who worship these deities, that claim is unsubstantiated when there is a defaced holy image serving as a banner on his blog.

In the adulterated image I am speaking of, Qudshu is digitally modified such as to be holding cutesy daffodils or yellow flowers of some sort. Worse than that, Rashap’s spear, the very spear he uses to safeguard this balance, these forces of life and death, is edited out and a box of disposable tissues is added in. The hand with which Qudshu would have held the transformative serpent is now reaching for the box of Kleenex which is destined to be filled with filth and thrown away in the trash. Daffodils are not the same depth of meaning as lotuses in this Egyptian image, and a Kleenex box instead of Rashap’s spear and Qudshu’s serpent? Wow. That’s not just insulting, it is dangerous. A smart person does not disarm a soldier and expect that soldier to act as guardian with a box of Puffs Plus with Aloe. A compassionate, decent person does not expect a soldier, a veteran of many wars, to wait on him.

The blogger basically projects himself into the image, positioning himself like Qudshu—a goddess whose name means Holiness—in the scene. In this adulterated image, Min is either handing the-blogger-as-Qudshu flowers, or the-blogger-as-Qudshu is shoving the flowers back towards Min because the flowers make the-blogger-as-Qudshu congested and s/he can’t stand their pollen. Keep in mind that pollen and semen serve the function of procreation, so in this image Qudshu is painted as symbolically rejecting abundance. Furthermore, as Qudshu, the blogger pictures himself as having a god of war and plague aiding him in wiping his nose. The priceless gifts that Qudshu would give are replaced with worthlessness: unwanted flowers in one hand, and paper trash filled with mucus in the other. The image may seem on the surface to be harmless and playful in its adulterated form, but it is not harmless or playful. The original image has been violated, robbed of its meaning.

Since the title of the blog in question alludes to its creator’s allergies, I can only assume that this is meant to poke fun at these circumstances while adding an air of borrowed ancient sophistication, an air of legitimacy, and pseudo-intellectualism to the blog. It is also warping a holy image to participate in the blogger’s self-deprecating joke about his allergies, a self-deprecating joke that looks more like a bid at false modesty to boost a human ego at the expense of the deities themselves.

In addition, the messed-up image probably acts as a mere nod–a nod which is actually the equivalent of the middle finger–to some supposedly-forgotten dusty ancient deities who the blogger may think no one on earth still takes seriously and which, to him, mean nothing more than puppets for his own amusement and mental musings. In messing with this image, he has taken these individual, real, living, viable, thinking, feeling, cognizant beings, and sets to erase them of their strength, depth, agency, and majesty. He pulls them into a pale, shallow, private world of impotent shadows of human thought.

With the altering of this image, the deities are treated with less dignity or thoughtfulness than an insect which a person may actually think twice about before swatting. This holy, powerful, ancient image is rendered into a thin watered-down joke about some human’s sniffles. The only thing here laughable is that we’re expected to believe that the person who would do such a thing would ever take our deities and our ways seriously, even when he says he does, and say something important about these things. If comedy and tragedy come together, then the tragedy is in allowing this blogger our time and our good faith, because his works only seek to erase the beings and the things we hold dearest.

I could go on about how hurtful this is to the deities themselves, to the ancestors, and to these deities’ people from priest to layperson, and to myself. I could go on about how much I cherish my relationships with my deities. I could go on about how meaningful the deities are, how meaningful the deities are to the world general, and how meaningful the deities are to me specifically. I could go on about the depths to which my gods have suffered on behalf of and because of humanity—a terrible, soul-aching, gut-wrenching suffering which I have witnessed. But what’s the use? My words will only be either ignored or twisted and used as verbal ammunition in this war that blogger has against the deities themselves, a war that blogger cannot and will not admit he has started. It is a war he has created out of his own fears and distrust of the deities and his own discomfort at being less powerful and occupying a stratum lower on the hierarchy than the deities.

Every time I go over to that blog, I am faced with the very glaring insult to my deities. The blogger in question has bastardized a sacred image, has kept it up there for a long time, and has done it for his own gain. Even if he took it down now, the damage is done. When he doesn’t even bother to treat a sacred image as valuable, he cannot convince me that he has anything of value to say about the deities whom he does not value and whom he has actively devalued in thoughts, in words, in deeds, and in imagery.

If it is not an “archaic” extremist militant group like Daesh trying to erase the gods of my tradition and my heart, and all of the gods of the lands of the Middle East, with propaganda, machine guns, jackhammers, or explosives, it’s “modern” and “rational” persons in the media or, as in this case, in mainstream Neopagan blogging, desecrating and trying to erase them through subtler, less obvious means. These latter are dirty and insidious means, which generally slip past modern audience’s emotions and critical thinking “radars” when the explosive damage of Daesh is more likely to be noticed and treated with the horror, the anger, and the acknowledgement the deities deserve, the ancestors deserve, and frankly we deserve, too. (I wonder sadly, though: is this notice because the explosions draw the attention of the “modern” West because of the horror done to the gods, or because of the statement of cowboy defiance against the West implicit in these acts?)

We all — beings from deities, to ancestors, to humans, to many other beings — we all deserve better. We deserve to see these situations made better as best we can manage for all involved. We can’t do that without seeing the truth of these assaults for what they are first; assaults not merely on remnant history or symbols but on the fabric of meaning and upon our gods themselves and the relationships held most sacred in this world. (And these matters certainly extend well beyond the deities of the Near and Middle East, but the scope of this writing specifically addresses these desecrations.)

There exist in our world many harms, and some are very obvious. Some are much more subtle harms, which can cause the same damage and erasure that Daesh can wreak, often without present notice at all. No bombs, no jackhammers, no machine guns aimed at the ancient artifacts which are images of the gods… “funny” manipulations and desecrations of an image accomplishes a similar goal of erasing the deities and desensitizing us to the wrongness in one blow.

Seeing either expression of harm, subtle or indelicately explosive, with too much frequency and without the guidance to recognize critically these horrors for what they are, has a desensitizing effect, an anesthetizing effect, on whole societies and ways of viewing and responding to the world. Over time it gets to be — has gotten to be — “no big deal”, when people act in these manners and further wreck the very relations we seek to heal, restore, and reestablish. We can’t fix these things when we can’t recognize that they got broken and are continually getting broken in the first place, and in the second and third and fourth as well. This misunderstanding of what is sacred and how to treat it combined with a desensitization to desecration, is the lasting symptom which continues to drive a wedge between ourselves, our deities, and the ancestors who could help us heal these matters within ourselves and our societies. It is a symptom of relationships which were poisoned long before we got here, and it is a symptom that we must learn to overcome lest we continue to live in the poison and propagate it, thus poisoning future generations. I pray to my gods, I pray to all our gods, that for all our sakes and the sake of the future that this is a matter which we, each and all of us, can overcome so that there is at least something sacred left for today’s children to inherit tomorrow.